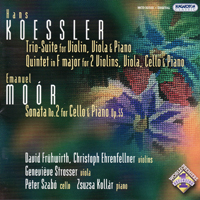

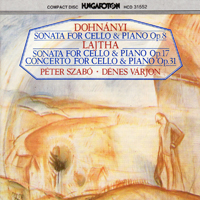

Rarities from the Hungarian musical history - on a Hungaroton recording

Here we are, another “first recording” of some pleasant chamber pieces of music. In between Hans Koessler’s Trio Suite and Quintet in F major there is Emanuel Moór’s Cello Sonata No.2; the performers are David Frühwirth, Christoph Ehrenfellner, Genevieve Strosser, Péter Szabó and Zsuzsa Kollár (but we can only guess which violinist we hear in the Trio Suite). The source of the quintet is a manuscript while the two other works also have a published version.

One can contemplate on the often unjustified selective activity of time – and decide from which direction to intervene into the history of culture. The world premier series of the Hungaroton Classics broadens the panoply of known authors and provides opportunity for the instrumentalists to be the performers of pieces presented for the first time – but whose presentation they are nonetheless familiar with, given that these ‘unknown’ composers are the contemporaries of the known ones they learned to play throughout their lives.

Hans Koessler’s name is known mostly from music history books – either from the material on the Music Academy’s institutional history or from subjective reviews about him as the teacher of the Academy student Bartók. The Kecskemét-born Emanuel Moór’s name is come across even more rarely. But supposing that it is indeed through his works that a composer can be best identified, we are richer again, especially regarding the era.

In retrospect we have an ability to differentiate more characteristically, with stronger markers than the general vernacular language of music must have presented contemporaneously. The examination of style orientations is naturally of utmost importance but we must be aware that no matter how sparkling and arousing, or on the contrary, stagnant and flat the part of the culture was, it definitely reflected its immediate environment’s effects differently from how we can, from any amount of data, reconstruct it now.

Listening to hitherto unknown pieces there are several ways we can be surprised. The most personal effect is exercised by the ones that offer a broadening of the musical vernacular. That is, a scope that provides us with knowledge- which does not make us better informed, but which makes us want to take further independent journeys into the music via notes or audible material. I am not talking about ‘wandering tunes’ or ‘lost property’ kind of musical quotations but about a kind of speech that through its vocabulary gives a feeling of the late composers. Also it teaches us about late performers, moreover, late audiences – since they belonged together much more closely then. The system of expectations, if it existed at all, must have worked entirely differently. We like to use the term – in a word-for-word translation from German – ‘after-feeling’ to identify what we cannot describe owing to the fact that it does not seem up-to-date due to a century’s distance from us. It is hardly soluble for instance to what extent Koessler’s Erkel-like phrase in the Trio Suite was conscious and whether it was meant to deliver some sort of a message – although I would rather say, listening to the energetic movements, that he simply possessed a rich musical vocabulary and seldom dealt with hidden messages and figurative senses.

The nursery rhyme of Moór’s Sonata for cello and piano, which any music fan of our time knows from both Mozart and Dohnányi, presents a similarly joyful revelation. The fact that these composers were not

willing to be language reformers but preferred to make the existing world comfortable for themselves and for their musicians gives us a homely feeling all the way through. In the meanwhile their pieces reflect

preparation, confidence of style, technical knowledge and last but not least, instrumental knowledge. They were also immediate as they did not work for their table drawers. The multi-functional being, which is not so far from the man of our time either, the necessity to bring together trade, profession and career is also something worthy of a thought – if they ever contemplated such matters. It is not a unique case that they lived so much for the present that like the grand masters of the past, they neglected the question of immortality. We might feel regret from the point of view of art and science that these composers did not have a list of compositions and thus they assisted in their own annihilation. Nevertheless, these works are interesting even if we are aware of the need for indulging in reconstructive puzzles.

The extensive opening movement of the Trio Suite is balanced against the rest of the piece (Romanze, Gavotte, Finale) almost by itself; the quintet gives space to a Minuet too, having been popular for such a long time; the cycle is wholly built from the succession of contrasting pairs of movements. The form construction in Moór’s cello sonata is similar to this, but here the real Scherzo is given second place.

Hearing these chamber pieces one cannot help drawing parallels with the art of painting and thinking about the immortal themes of 19th Century Hungarian painting which defy time; the still lives and landscapes that provided great opportunities for the painter to display his professional skills while obviously also enjoying the process of creation. The performers make us believe that although the noble tradition of home concerts were decreasingly popular, it was not confined to dilettante-amateur passing of time. Composers offered high quality material, which honour the performers probably merited. If we think

about it, Koessler’s Trio Suite was dedicated to such a great artist as Ernö Dohnányi and among the customers for Moór’s pieces there were plenty of world celebrities…

High art, even from such a long time ago, facilitates valuation for posterity; it provides a tool to pass on the musical inheritance of the past and make the artists of our time more widely known.

Katalin Fittler

Translation by Susan Kapás

Zene Zene Tánc

May 2005