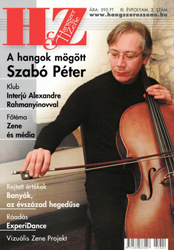

Music behind the sounds Interview with Péter Szabó

Péter Szabó is the solo cellist of the Festival Orchestra, he conducts, he writes cadenzas, he searches for pieces which have not been performed yet and then he presents them. He has won prizes from numerous international competitions. He is going to give a chamber music concert with Alfons Kontarsky and David Frühwirth in the Budapest Spring Festival. He has made recordings for Hungaroton, Naxos and EMI.

Music is behind the sounds --he claims. -- Interpretation is the exploration and understanding of this world. Music comes into the world in this realm and it continues living here.

Q. Why did you choose the cello?

A. My father, who was a composer, made me learn the piano in the beginning. My teacher's daughter played the cello and her instrument was always underneath the piano. I kept crawling down to the cello and trying to play it. They said if I was attracted to it that much I should also start learning the cello. I was four and a half years old then.

Q. What made the cello so attractive for you?

A. I liked its shape and sound very much; especially its shape. I did two majors before the finals, cello and piano, I took both final exams but I only applied to collage with the cello.

Q. Why did you not continue the piano studies?

A. There were two reasons for that. Firstly, at that time there was ‘numerus clausus’ in Romania: they limited the number of Hungarian students who could go to colleges and universities. Secondly, the Ceausescu regime supressed culture thus preventing the bringing up of reasonable beings. There was one single cello place in Transylvania and that is where I was accepted, the Cluj Academy of Music.

Q. You were taught by György Kurtág and Ferenc Rados. When did you start your studies with them?

A. I had been attending the Bartók seminar ever since I was a child. That is where I met them and Miklós Perényi. My whole musical approach was defined by the knowledge I had received from them. These relationships were more than teacher-student connections, I received a lot from them as a human being too. At that time it was difficult to study in Hungary as a Romanian citizen. There were times when I got off the train with four forints in my pocket. Professor Kurtág, who did not want to hurt my feelings, pushed a match box in front of me on the desk. Take it --he said. There was some pocket money in it. But I was also given a scholarship from the Hungarian State many times.

Ferenc Rados was my teacher later in the Ferenc Liszt Academy of Music, I studied chamber music from him and László Mező was my cello teacher. I follow the Casals tradition in my cello playing. Mező was a Casals student; due to the effect and connection, I feel as Casals was my grandfather. The most persisting characteristic of the Casals mentality is the discovery and preservation of values.

I learned that the essence is behind the sounds. All the power and meaning behind the piece is there, as well as the system of gestures --which to depict and express is the greatest mystery.

Péter Szabó's instrument came to Hungary in a very special way. The Romanian state at Caucescu's time wanted to impound this extraordinary cello together with other great instruments belonging to the family. For example a Steinway piano was almost seized too. At last the cello arrived in Hungary through informal channels in an adventurous way.

Incidentally, it was Csaba Szabó, the father, who bought the cello from the Brassai successors. At this time Sámuel Brassai, the renowned polyhistorian invited such prominent figures to Cluj as Bartók, Brahms, Joachim and Casals. On one occasion he bought a full quartet --all the four instruments-, whose first violin was a Stradivarius and the cello was this instrument made in the 1750s.

Péter Szabó nurtures relationships with Hungarian musical instrument makers, this time a copy is being made for him by Ferenc Kőrösi. The instrument is a Guidantus Floridante model, whose original the artist played on many occasions.

Q. Would you give an example of the system of gestures?

A. Beethoven's sounds are the sounds of love. His childhood was spent with an immeasurable lack of love. Still, this is what dominates his music, this is the basic characteristic of Beethoven's gestures.

Q. As I have heard, once during your high school studies, you were not allowed to leave the country.

A. I entered for a competition here in Hungary and three days before I was supposed to leave they decided that I could not go. I had been preparing for the competition for months and I knew the material lasting several hours very well. Instead I had to stay home and clean windows as part of the communal work.

Q. What was the Cluj school like?

A. This Academy showed the influence of the Russian school. High standards and professionalism dominated our work spirit.

Q. When did you move to Hungary?

A. In 1988. From 1985 our situation had became intolerable; both my father and my mother were dismissed from their jobs. That was when we decided to settle here.

Q. Was this situation due to your father's work as a Csángó-Hungarian collector?

A. Yes. Kodály had sent Lajtha to collect Csángó folk songs. After that, my father, Csaba Szabó was the first to collect Csángó folk songs. But the scientific work was pursued in resistance to the regime, basically illegally. The Csángó villages were sealed off hermetically by the Romanian police and police agents were standing at both ends of the villages. Only with permission could someone enter. My father slipped in between the gardens and he collected folk songs like this for years. This collection work and the Transylvanian Harmonic Songs all provoked the political regime's rage. The latter appeared in a CD-Rom format and won the Hungarian Academy's award.

The other political problem came from the fact that my father was the president of the Marosvásárhely department of the Society of Composers. They noticed that no pieces were created glorifying the system, so they indicated that these composers should also write Ceausescu cantatas and similar pieces. My father refused. That was when our situation became impossible.

Q. Having had moved to Hungary you very soon went to Salzburg.

A. When we moved here, I became the scholar solo cellist of the Philharmonics. Unfortunately this went on only for a very short time because the status was terminated with the re-organization of the Philharmonics. I felt that this decision was against culture - and I had experienced that before. I found it exasperating, because Hungary's strength had always lied in its display of outstanding artists. Then there was an audition for Sándor Végh's orchestra, the Camerata Academica in Salzburg. I went, I played and I got in. I was not alone in that, several others went too. That is how Adrienne Krausz got settled in Paris - where she lives even now.

The publication of Csaba Szabó's composing and scientific career is a complex task. A major part of the musical literature and publishing activity of Péter Szabó is the fostering of his father’s spiritual inheritance via the publication of his works.

Péter Szabó follows a life-like interpretation in his attitude as a performer. He aims at recording the pieces without large cuts. The flow and the intensity of the performance, the inspired moments which play upon the overall piece do not lose their complexity if we let them follow in their own progression.

Q. Later you were teaching at the European Mozart Academy too.

A. It was an extraordinary school. The idea originated with Sándor Végh and he was the one who carried it out. It was a post-graduate training of two years, where students could learn free of charge. They had to pay only for their travel expenses.

Q. You have been working with the Festival Orchestra for quite a long time. What significance does it have in your life?

A. The orchestra is a stable point in my life, it is an outstanding ensemble with excellent colleagues. The orchestra means a lot to an instrument player. Especially if the working relationships offer inspiration. The milieu formed by Iván Fisher is a fertile environment.

Q. You produce a great number of truly interesting recordings. The Pleyel concertos for example.

A. There was one known concerto which I took as the basis of my research. I knew that the traditions of the era necessitated the production of other cello pieces too. Pleyel was a remarkably interesting person anyway, he studied composition with Haydn and the Eszterházy family paid for his tuition. I relied on the catalogue by Rita Benton published at the beginning of the century and that is how I found the other concertos in Vienna, Paris and London. I received the works in a microfilm and the parts were written from these full scores. We recorded all the five cello concertos with the Erdödy Chamber Orchestra this way.

Q. You contributed to it both as a cellist and a conductor, moreover, as a composer.

A. Yes, I wrote the cadenzas. My father always led my musical education towards a more complex attitude. Beside the cello, I studied composition, piano and theory too. I keep conducting more and more often now. I am lucky, because my father was an excellent musician, I learned a lot from him and during my career I have met many prominent musicians. I started my musical profession as a talented child and, to my greatest joy, the tradition seems to continue: my daughter, now eleven years old, has already won many international competitions and now she is taking an entrance examination to the Academy.

Music is all that is behind the sounds and this world is inexhaustible in richness. I was given the opportunity to get to know this complexity. My musical activity is the exploration and interpretation of this miracle.

Máté Domonkos

Source: www.hzo.hu

Translation by Susan Kapás

Hangszer és Zene

February 2005