Fathers, sons and daughters - or the apotheosis of the musical vernacular

Pieces of Joseph Rheinberger, Hans Koessler, Emanuel Moór and Emma Kodály

(...)

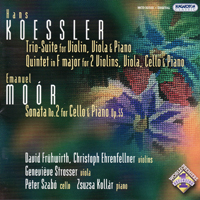

HANS KOESSLER

Trio-Suite (1922)

Nonett, op. 13.

Quintet in F major for two violins, viola, cello and piano (1913)

EMANUEL MOÓR

Sonata No. 2 for Cello and Piano (Op.55)

David Frühwirth, Christoph Ehrenfellner - violin

Genevive Strosser - viola

Péter Szabó - cello

Zsuzsa Kollár -piano

Hungaroton HCD 32331

Hans Koessler (1853- 1926), late composition professor at the Academy of Music in Budapest, had a wholly different creative approach towards the musical vernacular. His compositional fame is slightly faded due to the fact that he was not on good terms with his most skilled student, Béla Bartók. This is regrettable because, as for this Hungaroton album, he seems to be a composer with exceptional technical knowledge and fastidiousness. He is undoubtedly a follower of Brahms, but owing to his compositional consciousness, he far surpasses the average apostles. Moreover, sometimes the Koessler pieces provide technical and poetical explanation for the special and unusual solutions of some of the Brahms pieces -- such as the unconventional selection of tone for the movements.

(Surprisingly both finales of the Koessler works on the album are in 3/4 tempo.)

The curious selection of instruments (violin, viola, piano) in the A minor Trio-Suite (1922) as well as the F major Piano Quintet (1913) clearly demonstrates that their composer knew very well the greatest masters, especially the works of Beethoven, Schubert and Brahms. This music has two features where one can grasp the very essence of Koessler's creative character, the consciousness, which Kodály would most certainly label as " culture ". The first is the thematic work. The composer works very economically; he creates his asymmetric themes -- which are rooted in the song traditions, just like with Rheinberger -- to provide the base for the web of motives throughout the whole movement. The second feature is his attraction to bold modulations -- Koessler switches from one key to another and creates sudden turns of harmony with considerable joy and ease and not only in the development of the sonata form, but basically at any point of the pieces. The Piano Quintet adds to this with holding out Koessler's contrapuntal knowledge and virtuosity in instrumentation. The Gavotte in the trio-suite and the archaic minuet evoking Bach in the quintet show a historical, neoclassic tendency.

Koessler gives traditional format to his movements, where every part of the structure is clear and the recurring themes are always varied. Nevertheless , in complexity of forms, he cannot compete with his model, Brahms. Listening to Koessler's pieces we might venture the conclusion that it is the level of complexity that differentiates between the grand masters and the correct little masters. But in the case of Koessler, we have to draw attention to one more peculiarity. The Piano Quintet was composed two years after the Duke Bluebeard's Castle and the Trio-Suite appeared simultaneously with the most radical pieces of Bartók, the two Violin-Piano Sonatas and it only preceded the Psalmus Hungaricus by a year. But it is not the lateness which is truly surprising in Hans Koessler's pieces, as at this time another student, Ernő Dohnányi also followed the pattern of Schumann and Brahms in composition. The really astonishing factor in his chamber pieces is his steadfast commitment towards style and language –for one , who never questioned the grounds of this 19 th century vernacular, this was the only possible musical dialect.

Emanuel Moór (1963-1931) is a completely different case. He was born in Hungary but spent most of his life in Western Europe and America and in the history of music he is primarily remembered by his special two-manual piano. It is less well known that following his studies in Vienna and Budapest, he also worked as a composer -- and judging by the remarkably original, ingenious and individual compositional style of the 2nd Cello-Piano Sonata (1900 k.) on the Hungaroton album, it is clear that his compositional work sank into oblivion undeservedly.

With its traditional forms, late-Romantic harmonies, song-like thematic structures and archaic ambitions, this sonata, just like Koessler's chamber music pieces, also follows the path of Brahms. Still, it is striking how often the harmonies of Moór keep circling round, not heading anywhere, but back to itself -- which foreshadows the modernism of the 20th century. Moreover, the themes frequently turn into scales and sequences, or suddenly break off due to stops and pauses. The unfolding of the harmony is hindered by certain baroque elements, such as the unaccompanied organ points . The formation of Moór's themes cannot be regarded as noble -- at least in the Brahmsian-Koesslerian sense --, they rather evoke the lapidary Hungarian songs written in the style of a folk song. Emanuel Moór combines this with the great romantic traditions labelled by the name of Brahms, while he breaks down the whole with certain technical solutions.

The significance of Moór's Sonata is efficiently represented by the excellent interpretation of Péter Szabó and Zsuzsa Kollár. The carefully developed technique of the performance created a fine balance between the flat thematic parts of the movement, the archaic gestures and the romantic passions thus exhibiting the fragmented nature of the structure and the originality of the piece. Zsuzsa Kollár is more than a reliable partner also in the two Koessler-pieces. Apart from the occasional distonalities of David Frühwirth, the four strings with Christopher Ehrenfellner and Genevieve Strosser create a homogeneous sound while also maintaining an individual character. In the Piano Quintet it is particularly the viola performance of Strosser that provides the listeners with unforgettable moments.

(...)

Anna Dalos

Source: www.muzsikalendarium.hu

Muzsika

May 2006